Do We Live in a d20 Simulation?

I’ve always thought its interesting to consider what it would be like to live in a world govered by the types of game logic which we accept as standard fare in many video games. As a kid growing up I always loved Flatland by Abbott and wondered how I could tell if my universe was actually a torus. Today what I considered was

Assume you live in a world governed by the d20 rules (similar to Dungeons and Dragons), where every difficult action has a chance of success determined by rolling a 20 sided die, adding a number corresponding to your skill, then comparing this against the difficult of the task in question.

For instance if you are tossing rocks at a bucket with some skill, say a +3, and being a bucket at some distance the difficulty of this task is a 15, then 1d20 + 3 < 15 would be your chance to fail. In this case 12/20 rocks would miss the bucket.

Imagine an inquiring wizard starts to track events around him, how hard would it be to conclude that his universe operated off of d20 principles?

Consider that he can only observe the success or failure of obvious tasks, but would have no idea what exact bonuses he or any other person has. And also that he wouldn’t know the outcome of any particular d20 roll.

My first thought was that essentially if the wizard could throw millions of rocks at a bucket then his probability of success could either converge very closely to a multiple of 5, say 45.003%, or he could observe a number with no particular significance such as 48.786% hits on average. Excluding the possibility that after millions of throws his skill at rock tossing improves this information would seem to give evidence towards one case or the other. What I wondered though is how many rocks would need to be tossed in order to get good evidence, clearly 1 wouldn’t tell you anything, while an asymptotic number might sort it out.

I made a Python script to work out these probabilities based on Bayes’ theorem where my priors are either living in a world with no set restrictions on probability, or one where the possible distributions of events is discrete. To simplify it I first considered an easier problem

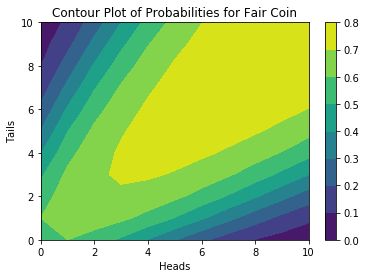

You either have a fair coin or a cursed coin. The cursed coin comes up heads with a specific but unknown probability p, how can you tell which coin you have after n flips?

This shows in a more quantitative way what you’d expect. A fair coin is pretty likely to give middling results. One advantage of comparing this against the cursed coin is that because the unknown probability $p$ can be anything between 0 and 1 with no real information known about it, this essentially integrates out of the Bayes formula.

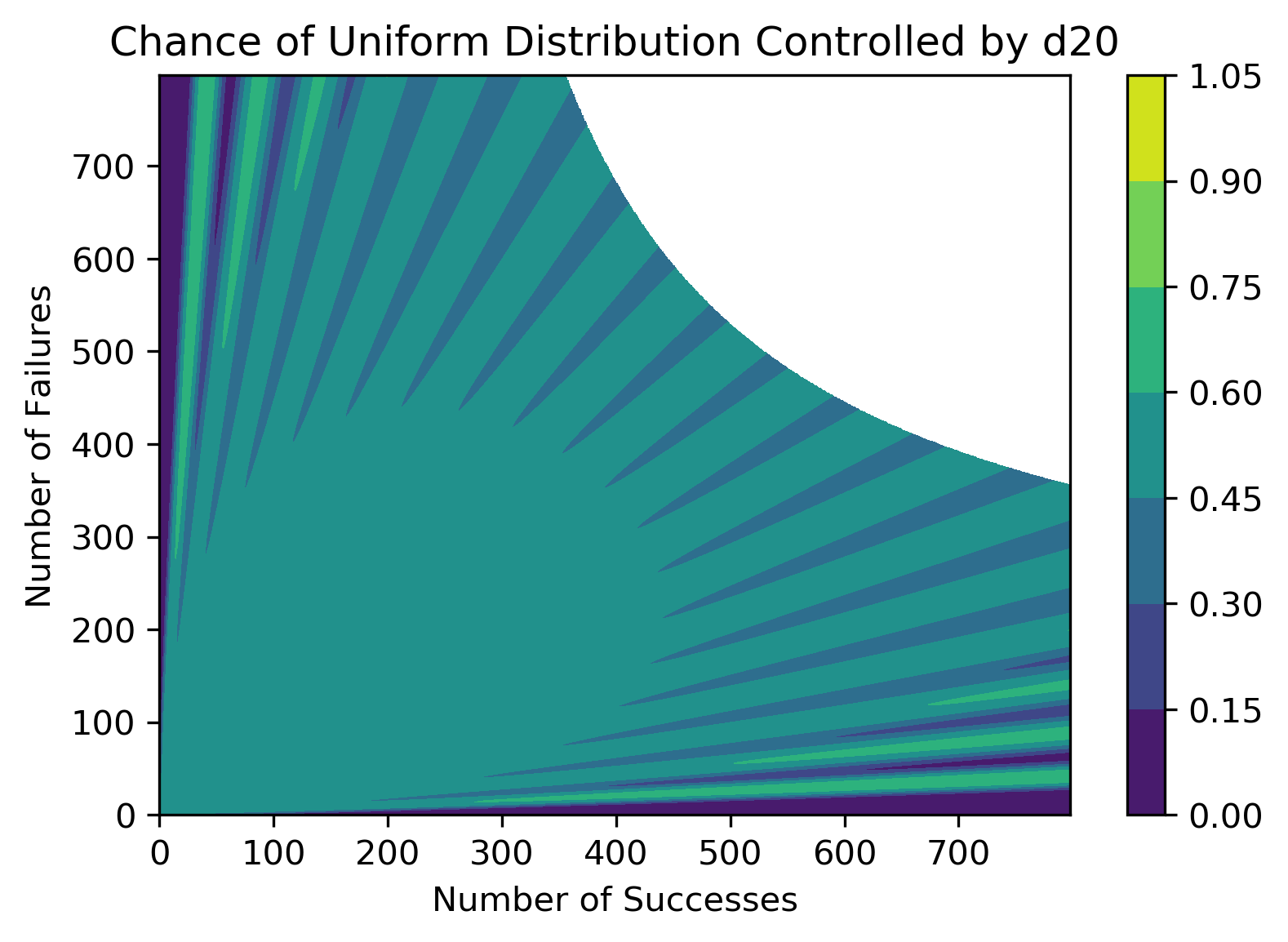

Expanding this to a world controlled by a d20 lands us with a graph representing the sorts of data the wizard might find.

After 800 rock tosses we can see a pattern emerging. The 20 stripes are starting to show us the areas where finding a probability which isn’t a multiple of 5 could be telling. Once again this confirms what seemed intuitively true and shows that the wizard will start to find some weak evidence even with data collection in the 100s, possibly enough for him to get his scroll published in a low-tier wizard journal if they have a poor statistical peer review process in fantasyland.

Meanwhile the big white area is telling us that we’ve reached some numerical limits on SciPy’s combinatorial function. The exact=True version has its own drawbacks, and I’ve tried a symbolic version using SymPy but performing tons of tons of these with perfect integer precision is both wildly unnecessary and very slow. The real solution might be to do more pen and paper work and sort the function out.

Unfortunately I have a creeping suspicion that this might boil down to one of the philosophical questions about how to use priors and apply Bayes. Essentially what this comes down to is, what does observing a number like 55% tell us?

- Nothing, because the possibility that this event happens with $p=0.55$ exists in both universes

- The d20 universe is much more likely, what is the chance that a real number would be exactly equal to some particular value?

I like how this is covered in Quantum Computing Since Democritus (who also seems to share a love of mad wizards obsessed with probability), but I think this may require some more mathematics and to consult with a real Bayesian legend. Until next time.