Debugging Python

The other day a question came up about the runtime of built-in Python functions, so I want to go through how to find out. What we’re going to cover is

- Understanding basic data structures

- Looking at the Python source code

- How to use a debugger to investigate running code

I’m hoping this will be a good introduction for programmers with a bit of background, but who are still learning about data structures and complexity. Also it was kinda fun to build Python from source and see how it operates internally.

The Question

What is the runtime of using [-1] to index a deque in Python?

Teaching someone Python they were wondering why deque doesn’t have a peek function to look at the last element. In order to look at the last element of a Python deque you can use indexing, d[-1]. What I didn’t know was what the runtime of using indexing on a deque is compared to what would be expected for peek.

Data Structures

Looking at the time complexity documentation on the Python wiki it has information for the member functions, but not for [] indexing. Although it does say that the deque is represented as a doubly linked list a sane assumption would be that it should have O(1) access to the last element.

Diving Deeper

But why assume when we can find out?

The Python source code is available, and a bit of Googling reveals that the implementation of deque is in the collections module. Take a moment to look over the code, the comments in the beginning have some interesting notes.

- Data for deque objects is stored in a doubly-linked list of fixed

- length blocks. This assures that appends or pops never move any

- other data elements besides the one being appended or popped. *

- Another advantage is that it completely avoids use of realloc(),

- resulting in more predictable performance. *

- Textbook implementations of doubly-linked lists store one datum

- per link….

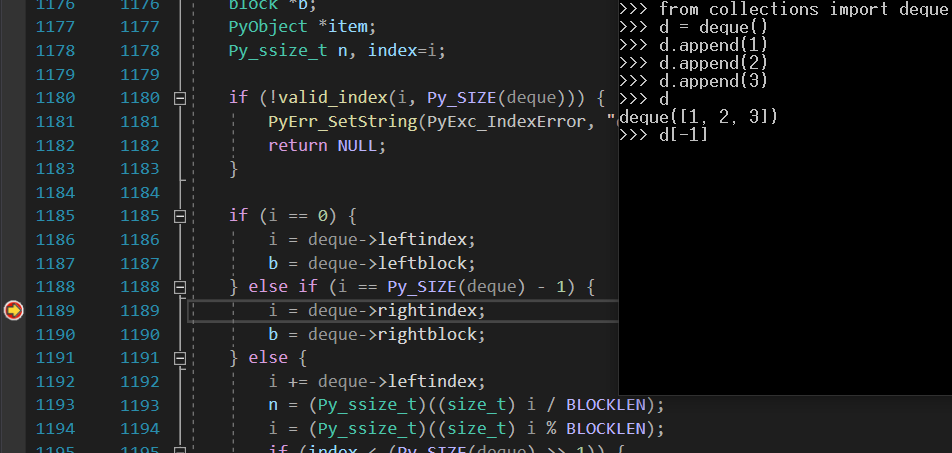

We’ll get back to that, but for now the main interest is in deque_item(dequeobject *deque, Py_ssize_t i) around line 1190. Reading this code it looks like there is actually some special logic for accessing the last element in the deque

deque_item(dequeobject *deque, Py_ssize_t i)

{

// ...

if (i == 0) {

i = deque->leftindex;

b = deque->leftblock;

} else if (i == Py_SIZE(deque) - 1) {

i = deque->rightindex;

b = deque->rightblock;

} else {

// ...

}

item = b->data[i];

Py_INCREF(item);

return item;

}

Seems pretty conclusive, but this does rely on a few assumptions. Is this the specific code which is invoked when indexing an item in the deque? How can we be 100% confident that the code does what it seems to do?

Run Python in a Debugger

Python is a program like any other, so if we run it with a debugger attached we can see how it actually operates. Doing this right quick we can see that

The answer to our questions is yes, deque has special logic which makes reading the end using [-1] a constant time operation. Lets go over right quick how you can do this too, and by extension answer any similar question about Python.

- Clone Python off of GitHub

- Build the project with debug symbols enabled

- Put a breakpoint in the target piece of code

- Run the Python interpreter with the debugger attached and see how it operates as you use Python

The first step is to download the code, using git clone in order to have a local copy of the source.

git clone https://github.com/python/cpython.git

Next I built Python using Visual Studio. The cpython docs have information on building it for all operating systems. The Visual Studio solution is under the “PCbuild” directory, but note that you will have to download additional dependencies before the project works (see the get_externals.bat part of the build instructions).

Once you are able to build the project you should be able to place breakpoints and run the code, which brings up an interactive Python prompt. If you are new to using debugging tools Microsoft has an introduction for Visual Studio.

Interesting notes on blocks

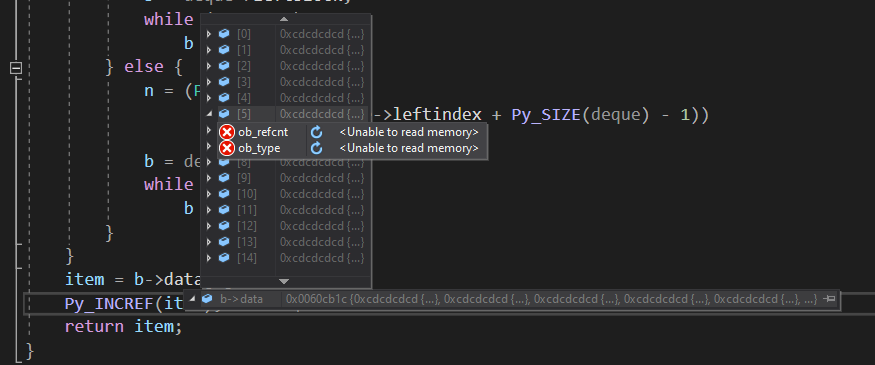

Following up on the comment earlier about “block sizes”, lets look at how the data is actually represented. We can do this by looking at what the b->data variable actually contains. In Visual Studio this can be done by looking at the Locals window, or mousing over the variable to explore what it contains.

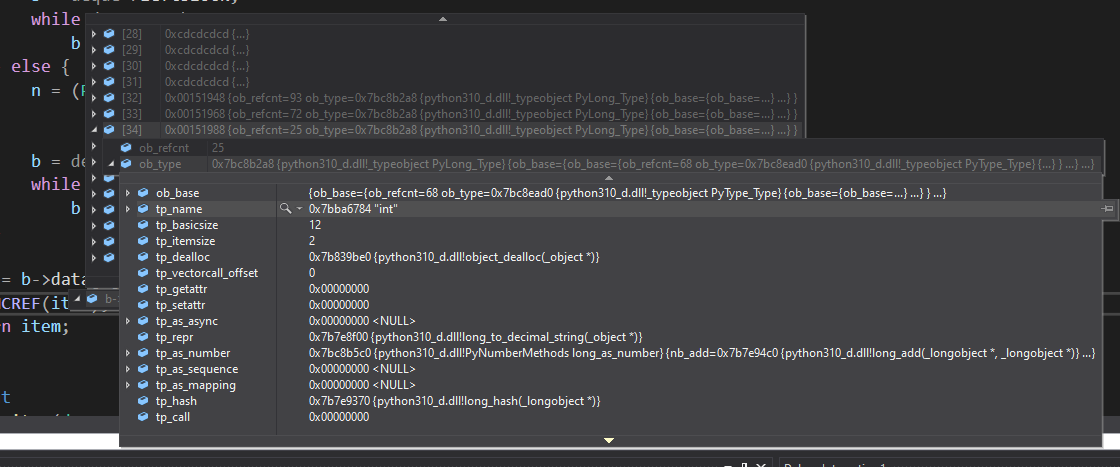

At this point we can see that the variable i == 34 and that data seems to contain copies of “0xcdcdcdcd” that when investigated have a red X saying that we are unable to read that section of memory. Usually what this means is that whatever memory is being referenced hasn’t been allocated by our program, and so the debugger is reflecting that its essentially illegal to use these memory locations. But since our code is looking at whatever is item 34 in this array we can scroll down to see that there are 3 items which have something different from the rest.

Which is what we would expect. When I first started testing out how Python worked I put 3 numbers into the deque, and here we have 3 items which have a “tp_name” of int. All making sense. So it actually seems that a deque isn’t a simply doubly linked list that “stores one datum per link” but instead are arrays of size 64 linked together. Interestingly it starts putting elements into that array at the middle, from the expectation that a deque can expand in either direction. So that means that as long as our deque has less than 32 items then accessing ANY of them will have an O(1) runtime.

If you want to test this try adding more than 32 items to an existing deque, put a breakpoint in the same area of code, and see how leftblock and rightblock differ after that. Also, can you find where that block sized is actually defined?

Follow through

I thought this was all pretty cool, but my main interest is in addressing the so-called “missing semester.” That is, I’m always looking for better ways to teach people on how to be able to answer these kinds of questions for themselves. Along those lines here are a few things I think I’d recommend anyone interested in learning more about creating and exploring code to look up.

- Look how cython allows Python to call C code. Programs being written in multiple languages is very common, such as the numerical libraries used in numpy or many .NET projects

- Understand how to use git and look at what open source projects are hosted online at places like GitHub

- Become more familiar with the debugging capabilities of whatever tools you use, both to explore code and check your own assumptions